Woody Allen is the film critic’s darling, and outside of directors, the role that critics love to talk about is cinematography. And with Allen, rightly so. Allen himself has never been the most technically minded, or technically patient, filmmaker. Yet he is meticulous about making beautiful films. The result is Allen usually allows cinematographers to leave their character on his film, but also often brings out their best work.

Although over 50 years, he’s racked up 16 cinematographers (or Director Of Cinematography or Director of Photography, as the role is sometimes called), his career has been marked by some famous collaborations.

Lester Shorr

Take The Money And Run (1969)

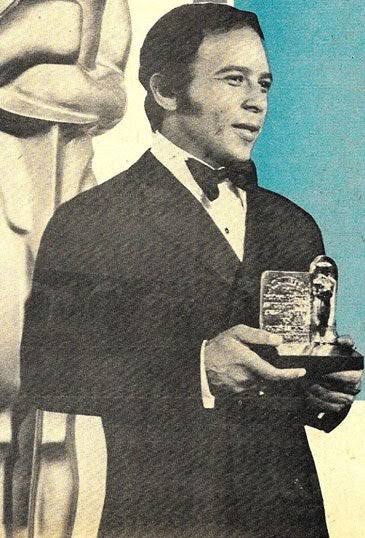

Allen’s relationship with cinematographers started badly, when a few weeks into production on his first film, Allen fired the cinematographer Fouad Said. Said had come from being a cinematographer on TV comedies like I Spy, and working with Allen would have been his first significant film credit. It’s never been made clear why Said was fired, but he did leave his legacy on the film. Said had invented the Cinemobile, a mobile film studio that fit in a van, and Allen continued to use it after Said left. It allowed Allen to bring the film in under budget, shooting several locations in one day.

Said was replaced by Lester Shorr, another experienced TV sitcom cameraman who actually won the first Emmy for photography in 1955. After working with Allen, he would go back to TV where he worked on shows like The Brady Bunch, Laverne & Shirley, The Odd Couple and much more.

Don’t feel bad for Said. Although he never again shot a film, he won an Academy Award in 1971 for inventing the Cinemobile, and he became a multi millionaire on the back of its success. He would then go on to work in finance, where he would become a billionaire investor.

We simply couldn’t find a photo of Lester Shorr.

Andrew M Costikyan

Bananas (1970)

For his second film, Allen hired Andrew Costikyan. It would be his most significant film credit. A year after working with Allen he was elected to Vice President of the Directors Guild Of America. When he died in 2012, his obituary said: “His death, like his life, was on time, under budget and very beautiful.”

There are lots of incredibly show-y shots in Bananas, and it’s an intriguing one time collaboration.

David M Walsh

Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex (1972), Sleeper (1974) – 2 films

David Walsh is Allen’s first returning cinematographer. He had worked on Evel Knievel (1971) but his work with Allen really put him on the map.

Walsh worked with Allen at a time where he was beginning to care more about what cinematography and production could bring to his films. Walsh initially turned down working with Allen because his first two films looked so bad. By the end, Allen liked working with Walsh so much that he wanted to continue the collaboration. But Walsh was unwilling to leave Hollywood. But it’s interesting that by this point Allen was already looking for long term collaborators. Walsh’s best work would come later in the 70s, in a series of films directed by Herbert Ross, written by Neil Simon.

Ghislain Cloquet

Love And Death (1975)

Allen shot Love And Death in France and Hungary, so he used a local cinematographer, someone who could communicate with the crew. He chose Ghislain Cloquet, who had worked on acclaimed films such as Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) with Robert Bresson and The Young Girls Of Rochefort (1967) with Jacques Demy.

It also showed that Allen was willing to work with a crew that didn’t speak English. He just let them do their job with a little talk filtered through translators. He would do this a few more times to the bemusement of his peers.

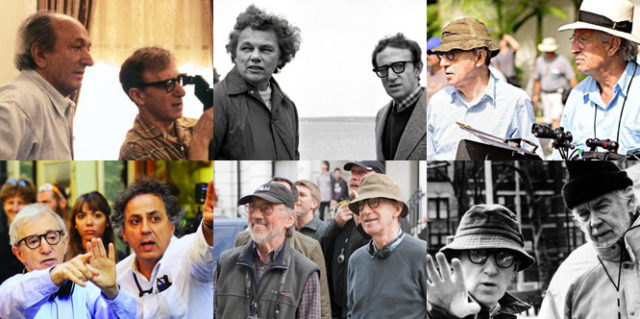

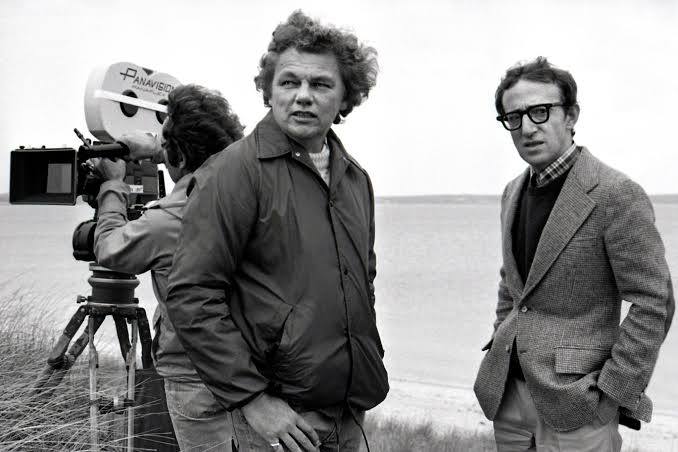

Gordon Willis

Annie Hall (1977) to The Purple Rose Of Cairo (1985) – 8 films

Gordon Willis changed the way Woody Allen made films. He was already an acclaimed cinematographer when he worked with Allen, having shot classics like The Godfather (1972) and All The President’s Men (1976). He was nicknamed the Prince Of Darkness because of his preference for low light. But with Allen, he would use the span of his technical abilities.

Willis brought a beauty to the screen, and guided Allen with blocking the scenes to make them more interesting. Essentially, the camera became an instrument in telling the story.

The two masterworks of Willis’ time with Allen are Manhattan (1980) and Zelig (1983). The first was shot in gorgeous black and white when it was out of vogue. The second was a technical masterclass of creating the looks of various film stock and special effects in the pre-digital era.

Willis would return to work for Francis Ford Coppola for The Godfather Part III (1990) and retired in 1997. He died in 2014.

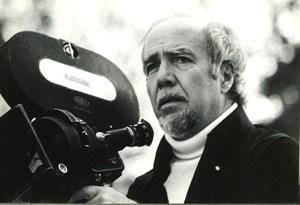

Carlo Di Palma

Hannah And Her Sisters (1986) to September (1987), Alice (1990) to Deconstructing Harry (1997) – 12 films

Carlo Di Palma holds the record for most films with Woody Allen. The Italian director was acclaimed in his homeland and was best known to English speaking audiences for shooting Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup (1966), and shot many classics of Italian Neorealist cinema.

Di Palma was very different from Gordon Willis. He was not as technically minded, and Allen affectionately called him a hunt and peck primitive. And through Di Palma, Allen could really bring his European influence to life.

The breadth of his work can be seen in the beautiful, nostalgic Radio Days (1987) to the abrasive and raw Husbands And Wives (1992). His films with Allen were beautiful in a different way to Willis. Di Palma moved the camera a lot more, and it allowed Allen to do even longer single shots that were staged with camera moves.

Di Palma’s health would deteriorate and he stopped working after making Deconstructing Harry (1997). Allen asked him to return for Anything Else (2003) and he started location scouting, but was not well enough to complete the picture. He died in 2004.

Woody appeared in a doco about Di Palma, released in 2018, called Water And Sugar.

Sven Nykvist

Another Woman (1988), Crimes And Misdemeanors (1989), Celebrity (1998) – 3 films (plus New York Stories, 1989)

Allen has long said he loves the films of Ingmar Bergman, and for a short run he used Bergman’s primary cinematographer Sven Nykvist. Nykvist worked on Bergman classics like Persona (1966), Cries And Whispers (1972) and Fanny And Alexander (1982).

After a long break, Nykvist worked again with Allen for Celebrity (1998). But during the production of the film, Nykvist was diagnosed with progressive aphasia. That film would be his last, and he was forced to retire. He died in 2006.

Allen appeared in a doco about Nykvist called Light Keeps Me Company, released in 2002.

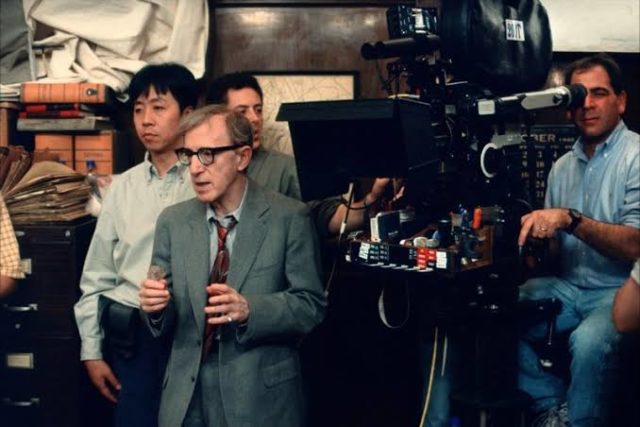

Zhao Fei

Sweet And Lowdown (1999) to The Curse Of The Jade Scorpion (2001) – 3 films

Like with Ghislain Cloquet and Carlo Di Palma, Allen wanted to work with a cinematographer more for their talent than their ability to speak English. Zhao Fei was best known for shooting beautiful historical epics in his native China, such as Raise The Red Lantern (1991) and The Emperor and The Assassin (1998). He had never worked outside of China before working with Allen.

Fei had to use a translator to work with Allen and the crew. But despite the challenged, he did incredible work, most notably with the way light is used on the great rooftop scene in Small Time Crooks (2000). The relationship worked well enough that it lasted for three films. After that, Fei stayed in China and never worked on another American film.

Allen would use the relationship of a foreign cameraman and a translator to comic effect in Hollywood Ending (2002). Speaking fo which…

Wedigo von Schultzendorff

Hollywood Ending (2002) – 1 film

Haskell Wexler was hired to be cinematographer on Hollywood Ending (2002). He was awarded the lifetime achievement award from the American Society of Cinematographers in 1993, for work on films like Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? (1966) and Days Of Heaven (1978). He was a big name and it would have been a return to working with an American cinematographer.

But it wasn’t to be. A week into production, he was fired. Apparently Wexler wanted to decide on shot angles, which is something Allen was used to having final say. Like he did in his first ever film, Allen dumped Wexler. It was the second time Wexler had been dumped from a film after it started. He was also fired from One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Next (1975).

Sent in to replace Wexler was German cinematographer Wedigo von Schultzendorff. He was in the US trying to make it in Hollywood, working on Igby Goes Down (2002). After this he would return to Germany and never with Allen or in America again.

Darius Khondji

Anything Else (2003), Midnight In Paris (2011), To Rome With Love (2012), Magic In The Moonlight (2014), Irrational Man (2015) – 5 films

When Carlo Di Palma dropped out of Anything Else, Darius Khondji was brought in. He started his career in France, and had shot incredible films like Se7en (1995) and Evita (1996). He would work with Allen on a bunch of European films, most successfully in Midnight In Paris (2011).

Khondji is one of the most technically beautiful cinematographers, and he was lucky to be tasked by Allen to make European cities look beautiful. Magic In The Moonlight (2014) in particular is one of Allen’s most underrated films, and as gorgeous as anything in his career. Khondji remains in demand from great directors like Wong Kar-Wai, Bong Joon-ho and more.

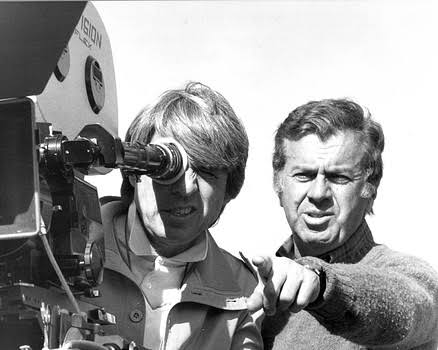

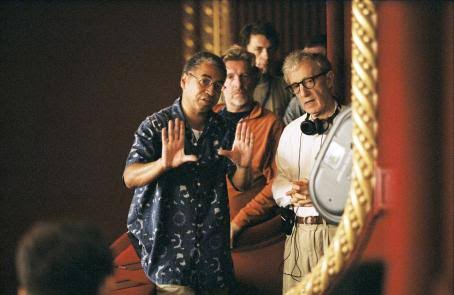

Vilmos Zsigmond

Melinda And Melinda (2004), Cassandra’s Dream (2007), You Will Meet A Tall Dark Stranger (2010) – 3 films

Vilmos Zsigmond was another established legend. His works included McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971), Deliverance (1972), Close Encounters Of The Third Kind (1977) and many more.

Zsigmond loved working with Allen, revelling in the long shots, beautiful locations and undemanding schedule. Both he and Allen were of a similar age and had started making movies as part of the American New Wave. They certainly looked like they enjoyed working together, and was Allen’s top choice in this time, location willing. It’s a pity that his three films with Allen are three of his most maligned.

Remi Adefarasin

Match Point (2005), Scoop (2006) – 2 films

Remi Adefarasin does not get the dues he deserves when it comes to Allen’s great cinematographers. He has one masterpiece with Allen – the cold, tense Match Point, bringing to life a London of elegance and brutality on screen. Before this he was best known for Elizabeth (1998), as well as a bunch of modern British comedies like About A Boy (2002) and Johnny English (2003).

Allen loved making Match Point (2005), and Adefarasin delivered admirably enough that Allen would invite him back for Scoop (2006). He’s still at it as of this writing, recently shooting the wonderful Fighting With My Family (2019).

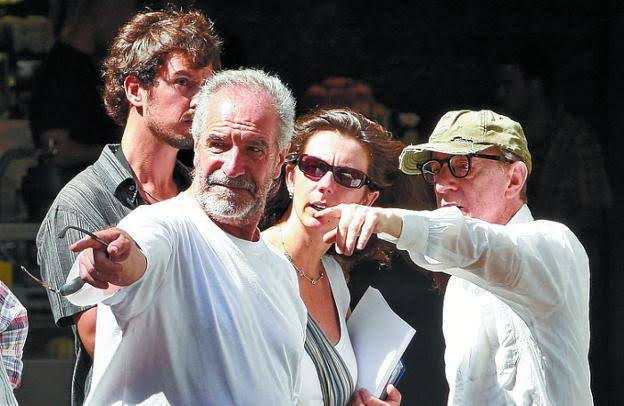

Javier Aguirresarobe

Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), Blue Jasmine (2013) – 2 films

If Vilmos Zsigmond was unlucky to have his hard work be part of three of Allen’s lesser films, then Javier Aguirresarobe hit the jackpot with two of Allen’s best. The Spanish cinematographer had mainly worked in his native country on acclaimed films like Talk To Her (2002) and The Sea Inside (2004). He was a natural choice for Allen’s first film in Spain, and Allen asked him to return for Blue Jasmine (2013), very different looking film.

Aguirresarobe has remained working on big American films including the Twilight films and Thor Ragnarok (2017).

Harris Savides

Whatever Works (2009) – 1 film

Savides was a New Yorker who was loved by a generation of American indie filmmakers. He did pioneering work with Gus Van Sant, David Fincher and Noah Baumbach. So it seemed like a good fit for Allen when he returned to New York for Whatever Works (2009).

Whatever Works looks wonderful, and shows a modern indie sensibility that makes less glamorous Manhattan neighbourhoods appear lovely. It seems at this time Allen changed between Khondji and Aguirresarobe depending on availability. If only Savides could have been added to that rotation. But sadly the collaboration didn’t continue and Allen would not make a New York set film for another eight years. Sadly, Savides died in 2012, aged 55.

Vittorio Storaro

Café Society (2016) to Rifkin’s Festival (2020) – 4 films

The latest in Allen’s long relationships with cinematographers is Vittorio Storaro. He is another cinematography legend, having worked on films such as Apocalypse Now (1979), Reds (1981) and more. Allen’s films at the start of the 2010s were gorgeous, but Storaro and Allen are creating a new language.

Firstly, Storaro has brought with him his preferred 2:1 aspect ratio. Reality has been thrown out over beauty, with films like Wonder Wheel exhibiting a striking glow that feel heightened and unreal. Allen and Storaro are really pushing the long shots, and using them more often, making the film feel more conspicuously like a series of plays.

They’ve worked together on four films, already putting him fourth in terms of most collaborations with Allen. It remains to be seen if they will work again together this year.

Eigil Bryld

Crisis In Six Scenes (2016)

The last new name to work with Allen is Danish cinematographer Eigil Bryld. The Danish cinematographer did great work on films like In Bruges (2008) and the TV series House Of Cards. However, he worked on Allen’s TV series Crisis In Six Scenes which was not Allen’s best work. The pair never worked again together.

Check out all our Every … In Woody Allen Films series.

3 Comments

All great. But when Woody says he sees no difference now between digital photography and film photography, I think he’s missing a filmic difference that makes his new millennium look shallower. It’s the difference between high definition and depth, often assumed to be the same thing. Autumn in Central Park still looks pretty in Woody’s new millennium, but the leaves on the trees have less texture, look less differentiated, than they did on film.

It’s been dormant for too long. Great to see this website active again!!!

Woody has always worked with the best cinematographers: Ghislain Cloquet, Gordon Willis (Prince of Darkness), Carlo Di Palma, Sven Nykvist, Zhao Fei, Darius Khondji, Vilmos Zsigmond, Remi Adefarasin, Javier Aguirresarobe, and Vittorio Storaro. Such an honor for them!